Book Update + My Thoughts on Generative AI and Writing

by Richard MacManusAn update on my Web 2.0 memoir (draft 1 finished!), plus thoughts on ChatGPT and its impact on society — especially on writers.

This month I finished the first draft of my “Web 2.0 memoir,” which weighed in at 153,000 words. I’ve been working on this book for the past eight months; every weekday, before breakfast in the early morning. My plan is still to serialize the book here on Cybercultural, which I’m hoping to start within 2-3 months.

Part of my goal for the second draft, which I began working on this week, is to cut it down to a manageable length. 150k+ words is too many — it’s almost enough to train a Large Language Model 😉

If you write books, you’re typically one of these two types: an outliner, or a “pantser” (flying by the seat of your pants, without an outline). I’m definitely an outliner! So I had a good idea of the structure and themes for this book before I started my first draft. But things always change during the process of writing a long work, so this week I re-architected the outline based on what ended up in the first draft. The themes are much the same, but I have a much clearer idea now of how each section of the book maps to certain years (the book covers roughly 2004-2012).

I like to think of a second draft as “shaping” the book into what it’s final version will be (or close to it). Kind of like a sculptor who gradually whittles away at the marble until the final artwork presents itself. Fortunately, with a 153k first draft, I have plenty of text on which to whittle.

Is GPT Intelligent and Can it Write?

Two things have made me ponder a lot this year about the state of writing, and creativity in general. First, of course, my book project, and how I plan to publish it. But also the rise of generative AI as the new hype cycle in the tech industry. The two are strangely interlinked in my mind, but I’ll explain why in a minute…

First, a quick primer on understanding “generative AI” apps like ChatGPT. The key insight is that they are powered by statistical models. They have no “intelligence” — at least not the type of smarts that a human has. What ChatGPT does, in very simple terms, is predict the most likely word that will follow the preceeding word, which it calculates based on the vast amounts of internet data it has ingested (175 billion parameters for GPT-3).

OpenAI’s GPT and all other “large language models” (LLMs) are powered by something called “transformers.” AWS has a good explanation that isn’t too in-the-weeds:

“The GPT models are transformer neural networks. The transformer neural network architecture uses self-attention mechanisms to focus on different parts of the input text during each processing step. A transformer model captures more context and improves performance on natural language processing (NLP) tasks.”

The phrase “self-attention mechanisms” jumps out there, at least to me. Perhaps because the main currency of Web 2.0 was attention (you’ve probably heard the phrase “attention economy” before). As a tech blogger in Web 2.0, my business goal was to get as much attention as I could — which in those days meant page views — which I would then monetize via CPM advertising (cost per thousand impressions). Of course, social media then took over in the 2010s, and attention gravitated from bloggers to influencers. I’m not sure if this has any relation to “self-attention mechanisms,” but — based on my own life experience — it’s what was generated from the neurons in my brain when I saw that phrase. But I digress…

“Attention-like mechanisms” have been a technique in machine learning since at least the 1990s, but for whatever reason it took until 2017 for the right formula to be found for AI applications. OpenAI’s GPT was directly inspired by a now famous 2017 academic paper written by mostly Google employees, with an unusually compelling title: “Attention Is All You Need.”

Fast-forward to February 2019, which is when OpenAI released its second-generation GPT. Whereas GPT-1 in 2018 had 117 million parameters, GPT-2 had 1.5 billion parameters. So it was a 10x larger language model. But interestingly, OpenAI had built an even larger model, which it decided not to release publicly. Here’s what the company said at the time:

“Our model, called GPT-2 (a successor to GPT), was trained simply to predict the next word in 40GB of Internet text. Due to our concerns about malicious applications of the technology, we are not releasing the trained model. As an experiment in responsible disclosure, we are instead releasing a much smaller model for researchers to experiment with, as well as a technical paper.”

GPT-2 was powerful enough, though, and it was clear at this point (early 2019) that it could create text at least at a “rudimentary” level.

“We’ve trained a large-scale unsupervised language model which generates coherent paragraphs of text, achieves state-of-the-art performance on many language modeling benchmarks, and performs rudimentary reading comprehension, machine translation, question answering, and summarization — all without task-specific training.”

Fast-forward again to June 2020, when OpenAI made available an API to GPT-3, which had 175B parameters. In an accompanying academic paper, released at the end of May 2020, it became clear that GPT-3 was a breakthrough in AI. Among its findings was that “GPT-3 can generate samples of news articles which human evaluators have difficulty distinguishing from articles written by humans.”

Later in the report was this statement, regarding the potential downsides of GPT-3:

“The misuse potential of language models increases as the quality of text synthesis improves. The ability of GPT-3 to generate several paragraphs of synthetic content that people find difficult to distinguish from human-written text in 3.9.4 [News Article Generation] represents a concerning milestone in this regard.”

So How Does All This Relate to My Book?

Let me say upfront: GPT-3 and above models are very, very good at text generation! Indeed, this form of AI, based on transformers and attention mechanisms, is rather helpful to my job as a tech journalist. I’ll often ask ChatGPT to summarize extracts from interviews I conduct, for example, and it is excellent at synthesising information and highlighting key points. I may also ask it to explain a complex technology to me, so that I can better convey its essence in my article.

But here’s the thing… GPT is not intelligent, and it is not creative in the way a human is.

GPT is basically predicting what it is I need, whether it’s a summary of some text or an explanation of something. ChatGPT has a vast store of knowledge to call upon in order to do its textual magic tricks, so very often its predictions are correct (except when it hallucinates; i.e. makes up facts).

However, there are two key attributes that GPT doesn’t have, which a human does:

-

Life experience, or more precisely the ability to learn from that experience — including, most crucially, your experience interacting with other humans.

-

The ability to create something unique and original, based on your life experience. Even better if this creation is an expression of your consciousness.

My book is largely a product of my life experience — in particular, my experience of building a Web 2.0 blog business from 2003-2011. Even if I “fine-tuned” GPT by feeding it everything ReadWriteWeb ever published as a giant CSV file, and then grilled it with questions about Web 2.0, it wouldn’t come close to the quality of content I have in my book. Not because my book is a work of genius (although it might be? who am I to say…), but because it contains so much of me in it — my emotions, my deep thoughts about that era of the web, the people I met and what I felt about them, my travel experiences, my feelings of what it was like to be alive at that time, etc.

For those reasons, my book is unique and original, since nobody else but me could’ve written it. An AI certainly couldn’t have written it, because most of the knowledge to do it is stored in my brain.

Now, I am willing to concede that my job as a tech reporter is more under threat from AI than my (as yet largely unpaid) career as an author. But then again, unlike AI, I can — and do — regularly talk to people in my industry, which helps me find out things that GPT doesn’t yet know. Even if GPT does know those things, I try to contextualize the knowledge I attain through my years of experience as a tech reporter and analyst. I have hunches about things, and I use my intuition a lot to figure out how technology will impact society.

None of this is to say that AI won’t eventually usurp me in my day job, but at least I’m confident about what I bring to the table as a human journalist (one that is increasingly augmented by AI, I should add).

Why I’m Writing a Book About Web 2.0

I mentioned above that GPT and writing a book are strangely interlinked in my mind. Here’s why: writing a memoir, or a book where consciousness is a key part of the narrative (which is most good novels, plus many great nonfiction works), is something an AI will never be able to do.

So that’s why I’m writing a book about Web 2.0, and why I hope many of you will enjoy reading it when I publish it.

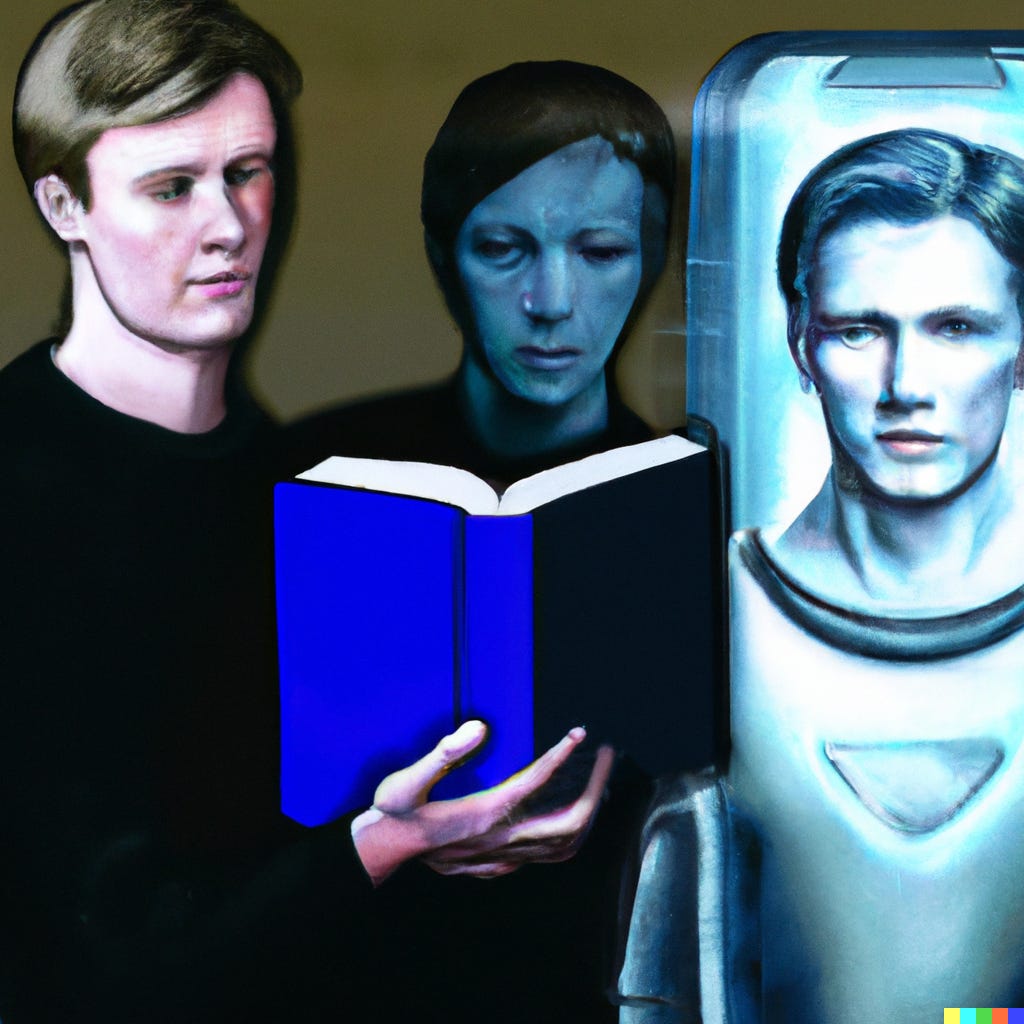

Lead image generated by DALL·E using the following prompt: “A science fiction painting showing a human writer and an artificial intelligence android”

Support Cybercultural

Cybercultural is a free newsletter, but you can also become a premium subscriber for £5 per month or £48 per year. Paid subscribers will receive the occasional bonus post, plus a thank-you mention in the paperbook book version of Bubble Blog.